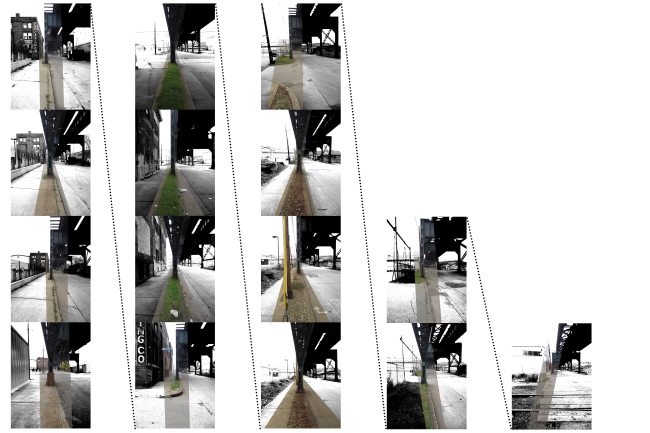

The median between the sidewalk and the road under the elevated rail crossing lower Laurencville is a threshold that changes: hard concrete, with grass only creeping through cracks; an intentional grass strip; a gravel strip, and then haphazzard edges of curb, train track, asphalt, grass, and gravel towards the end… the threshold visually feels stronger when it is reinforced above by the lower beam of a braced frame. There is not a wall, but the threshold implies a barrier between the realm of the street and the realm of the sidewalk. The barrier feels strongest where there is the planned grass median – the natural materiality is in strong contrast to the concrete and asphalt, and we are unlikely to walk across it. In contrast, the gravel feels more similar to the concrete and asphalt, making it easier to cross. The all concrete sidewalk and curb feels almost part of the street, with only grass growing through cracks, and the level change of the curb, marking any kind of threshold, so we are likely to cross into the street at any point along the road, and not worry pay attention to the threshold.

Movement = Incremental Change of Sensory Stimuli

In his essay “Representing Landscape,” James Corner cites Walter Benjamin’s assertion that we experience the landscape in a state of distraction. Our understanding of the landscape is the “sedimentation” of many fragments, perceived my many senses – not just vision. We often think of movement as continuous, and equate its representation with a plan view of a curving line… but the instant we see an entire path in plan, we have frozen it into a static object, removing the element of time. The experience of movement is better represented as sequential impressions of materiality and space. The above image emulates Mathur & Da Cunha’s drawing style in “Soak,” interweaving a panorama of the elevated rail in Laurencville with material impressions as one moves beneath it.

Kinesthetic Thresholds Are Topological

Starting to make drawings inspired by Mathur & DaCunha describing movement.

Nature, Infrastructure and Humans Interacting

This retaining wall, visually and acoustically separating the Eliza Furnace trail from the Penn Lincoln Highway along the Monongahela river, is is overflowing with plant life and artistic energy – an inspiring bit of creativity in an unexpected place.

Drawing Henri Lefebvre’s Space in Oakland

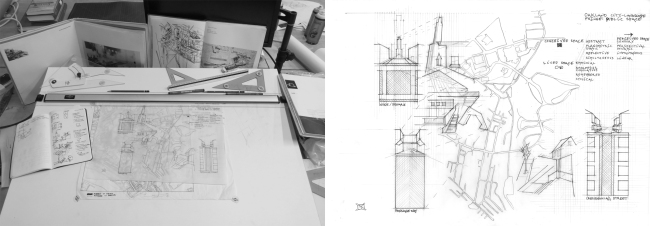

I am interested in exploring analytical drawings and hybridized media as a tool for investigation in my Thesis, inspired by the drawings of Morphosis, Daniel Libeskind, UNStudio, and others. Below is my description for the drawing produced above for my Urban Design Methods class:

Henri Lefebvre’s three categories for the production of space are: 1) Conceived (“the space produced by planners and political decision makers” – intellectus); Perceived (“the space produced by the spatial practice of all the users of a space” – habitus; and Lived (“the space produced by the invisible degree of people’s attachment to a certain place” – intuitus (quoted from Spatial Analysis assignment sheet).

I went for a walk around the perimeter of Central and South Oakland, observing the nature of the qualities of the space where the city meets the landscape. The actual city-landscape interface is almost mostly private, but I found three general conditions of public space in Oakland: A node or square that is a gathering point and directs energy inwards; a passage that is park-like but is used for passing through; and the street, specifically the road and the sidewalk.

All three public spaces are produced in the 3 different ways.

City planners or authorities from the universities have planned public spaces and streets (conceived space), producing a space that from the planner’s viewpoint is abstract, planometric, static, reflective, and existing simultaneously everywhere.

All the users produce perceived space through their spatial practices. Perceived space is sensory, perspectival, dynamic, instantaneous, and linear – the immediate experience of users at any given moment in the space.

Lived space is produced by all the users through their invisible attachment to the space. Lived space is emotional, amorphous, cumulative, remembered, and cyclical – it exists within each user, and it is not necessarily continuous, composed instead of various impressions.

Schwarzer, Zoomscape Ch. 1 (Trains) – Reading Report

Schwarzer, Mitchell: Zoomscape: Architecture in Motion and Media. New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2004

I will be doing weekly reports on my readings in support of my thesis. The images above are from my trip to Europe with the Burdett Assistantship in May 2013. I was paying a lot of attention to transportation architecture and the experience of movement in various transit vehicles. From left to right: Prague subway; view from Hamburg U3 (actually an elevated rail); View from ICE high-speed train en route to Dresden via Leipzig.

Ch. 1: Railroad

Summary:

-From the mid-nineteenth to mid-twentieth centuries, rail networks expanded rapidly across the landscape. They necessitated the keeping of universal time and schedules, oblivious to natural cycles of the days and seasons, in order to ensure effective travel.

-Rail travel completely changed the experience of movement through the landscape and the city. It deprived the non-visual senses while augmenting, but also distorting, the visual senses. Train movement makes it possible to see more, more quickly than by foot or horseback. There is an excitement of seeing buildings and landscape far in the distance rushing towards us, passing and than quickly receding behind us. The motion of the train is continuous, yet the eye of the passenger is always moving from one detail to another, from what is in front to what is beside to what is behind, unable to take in everything at once. The visual experience of the landscape becomes discontinuous. Buildings, features and impressions start to blur or overlap, creating a new urban-architectural landscape. Our eyes, the lateral views forced by the frame of the train car window, and the moving of the train fuse into a human-mechanical “panoramic vision.” We tend to focus on the horizon, or what is far, because we can see it; we ignore the foreground which has become an indistinct blur.

-Train travel changed the organization of the city and the landscape. Rail lines became divisions in the natural landscape. Trains exposed the industrial or poor backsides of cities.

-Urban rail transit has three variations: street cars, which move more slowly and at the level of the street, connecting passengers more intimately two street life; subways, which abstract the city into stops with an amorphous dark space of anticipation inbetween, and elevated rail, which gives passengers a novel perspective of the city and an intimate, almost tactile engagement with the architecture as it passes near it. When a rail makes the transition from underground to above ground, the spectacular site catches passengers’ attention (as in Boston).

1+3+9 Thesis Statement

Geoempathetic Transit:

Synchronizing Movement with Landscape

1) The speed of modern transit psychologically disconnects humans from the landscape.

1) Pedestrians can experience their environment with all of the senses, giving them a greater appreciation for the beauty and value of nature, as well as a sensitivity to the subtle daily, seasonal, and long-term changes in the dynamic urban landscape. 2) Walking allows humans to understand the landscape as a continuous surface linked together by rich experience. 3) By contrast, the ocularcentric, spatially isolated experience of the landscape from a train or automobile fragments the earth into destinations, reached in a stable, seemingly static transport space.

1) The spatio-temporal disjunction between destinations and the landscape between them enables the selective consumption of places and ignorance of the interconnectedness of the total urban-ecological system. 2) Without a strong connection to place not as points but as surface, we cannot hope to achieve a more holistic understanding of landscape. 3) Achieving that understanding of landscape, through richer perception of the journey, may encourage more sustainable practices in our daily lives, by causing us to empathize with the landscape – that is, to project ourselves into the forms of the landscape, and also to allow the forms of the landscape to shape our own psychophysiology. 4) A new movement corridor connecting the Monongahela and Allegheny rivers via Panther Hollow, Neville St, and the Bloomfield valley could function as a public space that engages people with the landscape. 5) The landscape will be manipulated to topologically organize multiple modalities of movement – walking, cycling, a (partially) subterranean rapid transit rail and a slower, street-level tram. 6) Pathways of movement will be choreographed to reveal the geological, industrial, and ecological history of the landscape. 7) Architectural interventions will shape the movement corridor into a responsive environment that registers, at multiple time scales, movement and change, both of people and nature, attracting attention to the landscape. 8) All of the senses – olfactory, tactile, thermal, aural, and visual – will be stimulated in a sequence of experiences engaging humans at various speeds – from that of the pedestrian to that of the tram. 9) A stronger empathetic relationship to the earth will be encouraged by slower movement, imbued with richer sensory experiences, revealing the history, present, and constant change of the urban landscape, to the mutual benefit of humans and of the total ecological system.

The panorama is of the northern end of my site, a valley feeding into the East Busway – the section is awesome, with steep and terraced slopes, a train track, and an elevated road for buses that I can imagine transforming into a sort of Highline for bikes and pedestrians… This space could become a public park with a screen for Pittsburgh filmmakers to host outdoor movies. Right now it is completely inaccessible to bikes and pedestrians.

Humans, Nature and Industry Interacting

Thesis Website Launch

Hi everyone!

Please excuse the appearance of my website while it is under construction.

My first post is a collage I made in my third year site studio, where I took inspiration from the interaction of an abandoned rail bridge, nature, and local fishermen in post-industrial Pittsburgh. Now my Thesis is investigating the spatio-temporal disjunction between humans and the landscape created by the speed of modern transit.